Background: Learning to Recognize Disability and Developing a Cross-Disability Consciousness

“People who don’t work in disability have a hard time identifying who has a disability. It’s vital to know what the right questions to ask to identify disability are, so the correct accommodations can be provided immediately.”

Susan Kahan, University of Illinois at Chicago Family Clinic & Chicago Children’s Advocacy Center

“Communities of color aren’t talking about disability in a way that youth can identify with what their body does, how it responds, and what you need in order to be a fully accommodated person in these spaces. So I believe that is what leads these youth in front of police, especially when you don’t have the services and supports you need just to be yourself.”

Candace Coleman, Racial Justice Organizer, Access Living

The starting point for systems and community change, from a cross-disability standpoint, begins with acquiring the ability to see disability in all its forms, existent in every community and throughout every walk of life. The following section offers tools to better see where disability is, and just how complex it can be.

A. Definitions of Disability

In the United States, disability is most commonly defined according to the definition under the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), a civil rights law that was a major milestone in the development of the disability movement. The ADA prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities and broadly applies to public accommodations, employment, commercial facilities and transportation and is applicable to the United States Congress.[9] In public use, it tends to be the most commonly cited law related to disability rights.

The ADA defines a person with a disability as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activity. This includes people who have a record of such an impairment, even if they do not currently have a disability.[10] It also includes people who are “regarded as” having a disability. Coverage of disability was expanded under the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 to include “intermittent disabilities,” such as epilepsy, which were not clearly included originally.[11] The amendment was intended to ensure that courts did not define disability too narrowly and that areas such as epilepsy, cancer and diabetes were covered. In other words, the act was intended to ensure that the ADA’s definition of disability was indeed broad.[12]

The ADA is applicable to “all activities of state and local government” regardless of funding source. This means a government agency cannot “opt out” of providing disability accommodations. The ADA thus applies to criminal justice entities – including but not limited to attorneys, courts, jails, juvenile justice agencies, police, prisons, prosecutors and public defense attorneys. Title II of the ADA requires that all state and local governments “give people with disabilities an equal opportunity to benefit from all of their programming, services and activities.”[13]

The 1999 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Olmstead v. L.C. is based on application of Title II of the ADA. It requires entities to avoid unnecessary institutionalization and confinement of people with disabilities.[14] Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg issued the decision in Olmstead, holding that the ADA requires people with mental health disabilities to be in the least restrictive, community-integrated settings.[15] In the context of Olmstead, it is critical to understand that jails and prisons qualify as institutions.[16]

Prior to the ADA, the major piece of law that protected the rights of people with disabilities was Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Section 504 is a broad application of disability protections under federal law. It held that essentially, any entity or program receiving federal funding could not discriminate against people with disabilities.[17] This includes criminal justice entities.

For the purposes of the Social Security Administration and its benefits, disability is defined differently. If an incarcerated person is receiving Social Security payments, benefits will be suspended if they are admitted to jail or prison for more than 30 continuous days. If an incarcerated person’s confinement lasts for 12 consecutive months or longer, their eligibility for Social Security Supplemental Security Income benefits will terminate and they must file a new application for benefits. This contributes to great difficulties for the person’s re-entry process.[18]

It’s also key to know that some existing law that focuses on institutionalization of persons with disabilities specifically names jails and prisons as sites of institutionalization. The Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act of 1980 (known as CRIPA) empowers the Special Litigation Section in the United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division to investigate and prosecute complaints in terms of this legislation.[19]

Disability, as a U.S. legal definition, can be masked by the many terms and phrases that are or have been used in society regarding people with disabilities. Terms and phrases such as “special needs,” “differently abled” and “crazy,” and other outdated terminologies such as, “handicapped” or “retarded” can convey stigma, a patronizing perspective or simply outdated values. It’s important to see disability as a neutral term, neither good nor bad, simply one facet of what and who a person is.

“Don’t look at me with pity. I earned this wheelchair. I own this wheelchair. I’m proud of it, and I’m going to use it to get places a hell of a lot faster than you could ever run.”

U.S. Senator Tammy Duckworth

B. Looking at Disability by the Numbers

How many people with disabilities are in U.S. jails? It depends. Disability demographics can be hard to pin down. Whether a person with a disability is counted can depend upon the definition of disability used, whether the person is willing to self-identify, whether a professional has labeled or diagnosed someone and, finally, whether disability is included in the design of demographic tools and questions. Demographic parameters can shift for a number of reasons and opportunities for data collection can be overlooked.

Outside of jail settings, the best estimate of the percentage of people with disabilities is about one in five.[20] In 2018, a United States Census Bureau data report said that, based on the Social Security Administration’s definition of “disability,” 85.3 million people ages 18 to 65 in the United States have a disability and 55.2 million people have a severe disability.[21]

Let us now look to these statistics in the light of jail incarceration. Statistics gathered from the 2011-2012 National Inmate Survey administered by the U.S. Department of Justice showed that an estimated 40 percent of individuals in jail self-reported having at least one disability.[22]

University of Michigan professor and attorney Margo Schlanger elaborated on these statistics while researching reasonable accommodation barriers for people with disabilities who are incarcerated. Schlanger explains that most people in jails have at least one disability, noting more specifically that approximately 40 percent have a chronic medical condition, 6.5 percent are deaf or have low hearing, 7.3 percent are blind or have low vision, 9.5 percent have an ambulatory disability and 60 percent have mental illness.[23]

“The numbers mean that how jails and prisons deal with disability is far from a niche issue,” Schlanger pointed out. “Rather, choices relating to disability are central to the operation of U.S. carceral facilities – their safety and humaneness, and their success or failure in facilitating the pro-social community reentry of prisoners who get out.”[24]

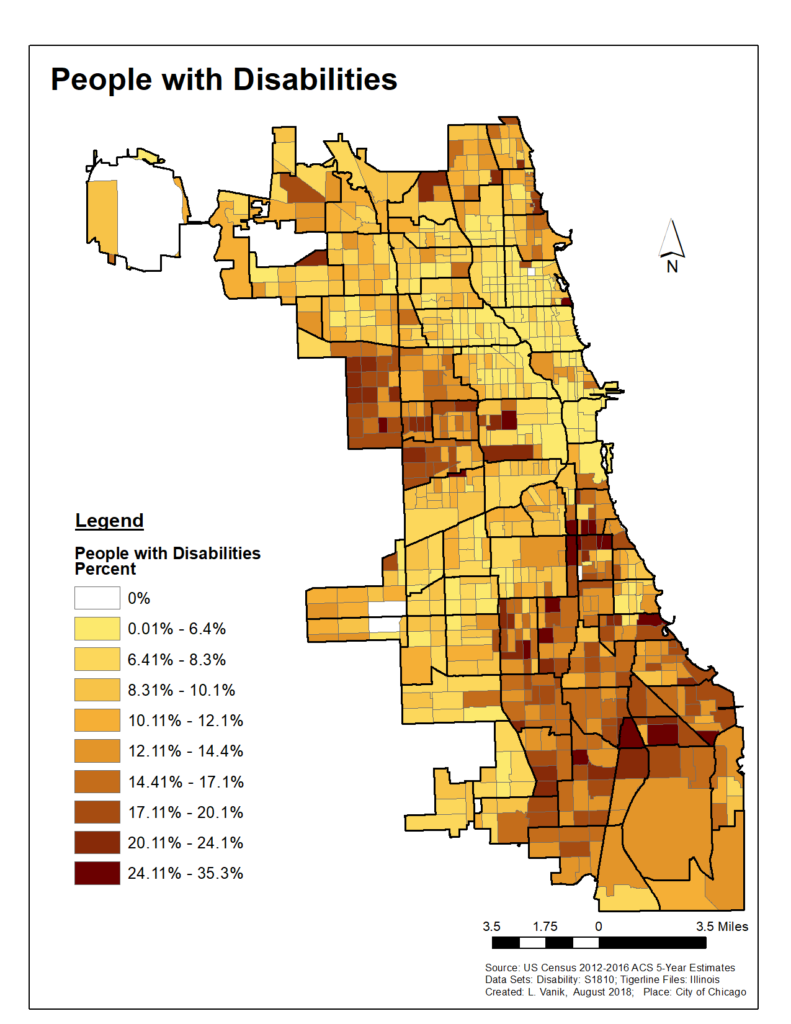

According to 2015 American Community Survey data, in Chicago, people with disabilities are more concentrated on the South and West sides. Most of the areas highlighted on the map below are also neighborhoods where poverty rates are higher and are primarily communities of color.

People with disabilities are collectively the largest minority group, totaling 61 millions adults, in the United States[25] – at least when you look outside carceral settings.

C. The Roots Are Intertwined: The History of Systemic Segregation

Race and poverty are major contributing factors to over-incarceration of certain populations. When you combine disability, race, poverty and family incarceration, the odds of police contact and incarceration increase.[26]

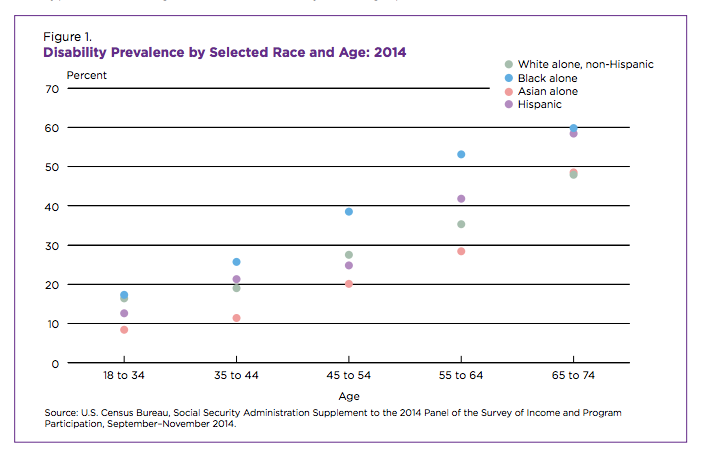

Nationally, Native Americans have the highest rates of disability among working adults, followed by black people at 11 percent; white people, 9 percent; Hispanic people, 7 percent; and Asian-Americans, 4 percent.[27] People with disabilities account for one-third to one-half of all the people killed by law enforcement.[28] When discrimination and bias overlap with other marginalized identities, an identity may become lost or mislabeled and therefore the story is never accurately accounted for, especially when it comes to race and disability.

Notable are the slightly higher rates of disability reported for black people in the United States. According to the study Black-White Differences in Self-Reported Disability Outcomes in the U.S.: Early Childhood to Older Adulthood, black people experience higher percentages of learning disabilities; for all disabilities in midlife, black people have 1.5 to two times the odds of disability over white people.[29] Disability advocates we spoke with attributed disability discrepancies across race to historical harms to communities of color, including the legacy of enslavement and lack of access to equal educational opportunities.

“Disabilities are intergenerational in impoverished communities. So the conditions and the lack of education, the crime, and the ignorance and the poverty lends itself to the next generation of broken families. And, you know, that’s it basically, the harm, the historical harm.”

Patrick Pursley, Impacted Community Cember

Michelle Alexander’s influential book The New Jim Crow points out that mass incarceration occurs for two reasons. First, law enforcement personnel are given vast discretion of where and whom to police. Second, the court system and laws are set to force a person who claims racial bias motives for their criminal justice involvement to “offer, in advance, clear proof that the racial disparities are the product of intentional racial discrimination.” The media and many Hollywood producers have put forth a false narrative, portraying young black men as violent and dangerous and people to be feared. The media at times functions as a lamp or a mirror to societal problems and stereotypes. These stereotypes are perpetuated through repeated exposure to disparaging images and messages.

This discriminatory stigmatization has carried over into households, police stations and our courts, in terms of sentencing trends. Simultaneously, the stigma of mental health has falsely portrayed people with mental health issues as scary and vile. By exiling certain populations from our communities, we devalue their lives, their belonging and their invaluable contributions to society. As one impacted community member said, “I think the fear of government puts my community in this sense of paranoia.”

In the United States, we incarcerate people of color and, particularly, young black people at astonishing rates. Black people are incarcerated at a rate five times that of white people.[30] One in three black men in the United States faces incarceration at some point in their lifetime.[31] That takes only race into account; when we look at disability, the numbers are also staggering. People with disabilities are represented in jails and prisons at higher rates than non-disabled individuals. People in jail are six times more likely to report having a cognitive disability than the general population.[32] It is not unfathomable to presume that there is significant overlap between race and disability, especially when we take into account the historical harm perpetuated against black communities in the United States.[33] A black child is six times more like to have a parent incarcerated than a white child.[34] Children who have or have had an incarcerated parent are more likely to develop attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), post-traumatic stress disorder, asthma, anxiety or depression.[35] In fact, 35 percent of trauma survivors develop learning disabilities.[36]

“Every time I go into the [Cook County] courtroom, I get disgusted because the majority of people there fighting the cases are black, a few whites, a few Latinos, and all the personnel is white. You go to the prison and it’s the same thing, but that’s an issue nobody wants to talk about.”

Ray Robinson, Community Leader and Impacted Community Member

In the 1980s and 1990s, Black disability activist Leroy Moore worked to shed light on the issue of police brutality and the over-incarceration of people with disabilities in California. Through his work, he educated parents of youth with disabilities who were facing criminal charges on how to discuss the topic of disability in their criminal cases. Leroy traveled the state educating judges and juries about disability. “They had no clue when it came to disabilities,” he said. Leroy also works closely with POOR magazine. The non-profit publication based in Oakland, Calif., holds a workshop called “Never Call the Police.” It teaches people in intersectional communities to create stronger bonds to achieve the goal of avoiding the need to call the police.

“I believe in police and prison abolition – because it causes deadly harm to communities of color and disabled communities. There is no such thing as a humane jail or prison.”

Lydia X. Z. Brown, Disability Justice Activist

Today, increasing numbers of disability advocates are calling for an intersectional understanding of how incarceration is impacting, in particular, disabled black and brown communities.

D. What is a Cross-Disability Approach?

“We are all very different and powerful, and unfortunately, largely separated and taught to be separated by disability type.”

Cathleen O’Brien, Housing Organizer, Access Living

Historically, different types of disabilities have been treated in a siloed fashion, usually by providers and policymakers. Deaf problems are handled by people focused on deafness and hearing loss; barriers for blind and visually impaired people are handled separately; barriers for people with physical disabilities are handled by people who focus on physical disabilities. This silo effect is reflected in everything from the design of Medicaid waivers for different disabilities to lawsuit settlements that outline certain disability types to be served to nonprofits that focus on single disability types.

Disability, by and large, tends to be identified and defined by the system or resource a person may be trying to access more than it is defined by any other standard. This is the bureaucratic framing that leads to viewing disability as a series of lists. However, there is another way to look at disability which is more practical than memorizing disability types or an etiquette list: the cross-disability approach.

“Cross-disability” as a term is defined by the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 as primarily applicable to Centers for Independent Living (CILs), which are disability services and advocacy organizations run and governed by a majority of people with disabilities. Access Living is a CIL, and as such we are required to strive towards a cross-disability approach in both our programs and in the actual design of our organization itself. Not only do we serve people across a range of disabilities, we embody a cross-disability approach in that our staff self-identify as having a range of disabilities. This has serious impact on our workplace culture and our commitment to disability reasonable accommodations.

As we practice it at Access Living, a cross-disability approach is a matter of core values, a commitment to not leaving anyone behind and recognizing that people may experience multiple disabilities at the same time, as well. Functionally, a cross-disability approach means that staff are prepared for inclusion by the probability of any kind of disability crossing one’s path and is willing to support people across disability types. No one disability type is more important than another. However, because disability comes in an infinite variety of forms and progressions, those engaged in a cross-disability approach have to commit to an ongoing process of learning and problem-solving towards supporting and including people with different disabilities.

Furthermore, a cross-disability approach is one that looks at all people with disabilities as a whole, regardless of disability type. A cross-disability approach recognizes that there are aspects of the disability experience that people with disabilities share to at least some degree. Some examples of these aspects are experiences of lack of access or discrimination, or using disability as a creative catalyst to solve social problems. Although access needs may greatly differ among us, our access needs are the common factor requiring a cross-disability approach.

What we at Access Living have learned is that a cross-disability approach is one that holds that society is in fact better when diverse disabilities are supported and included in social processes, because of the interpersonal wisdom gained and problem solving achieved. A cross-disability approach requires the flexibility to individualize supports. This is the cross-disability approach we strive to exercise at Access Living. Most of the time, in those interactions from a cross-disability approach, we are not asking those with disabilities to “prove” themselves with medical documentation. We simply remain open to asking what they need, being asked for support and committed to ensuring that that support happens. We aim to presume competence and to trust what people tell us they need.

“Without all the pieces it’s impossible to understand the full picture.”

Efferson Williams, Impacted Community Member

A cross-disability approach means being open to the idea – every day – that you will encounter people whose disabilities you do not know or understand, and from whom you are willing to learn. This openness is also fertile ground for innovation in looking at how social structures and programs can better serve all of us.

Back to the silo approach: when the general public refers to people with disabilities, many times they are coming from a standpoint of discussing physical disabilities, such as a person who has mobility limitations and uses a wheelchair as an accommodation. Other times, and most often in criminal justice fields, when efforts to make accommodations are emphasized, officials are referring to a population of people with mental health disabilities or substance abuse issues, specifically.

Where criminal justice reform buys into a silo approach however, opportunities for innovation may be lost. Addressing mental health without also addressing physical disability is not a complete approach to meeting a person’s needs and potentially limiting or avoiding jail incarceration altogether. Addressing chronic pain without also addressing traumatic brain injury is likewise an incomplete approach. Dealing with substance abuse recovery without also accommodating a person’s deaf status is, again, incomplete. There are far too many people who have contact with law enforcement and who are/have been incarcerated and have multiple disabilities that require the flexibility, access and creativeness of a holistic cross-disability approach.

Efforts at reducing jail use or jail incarceration will not be complete until the cross-disability conversation is fostered towards innovations that meet everyone’s needs.

A cross disability approach, after all, is ultimately about the conversation we have to have with ourselves about the place of disability in our world. To fully view disability in a cross-disability sense and to fight back ableist tendencies, it is crucial that we delve into what disability means for us personally, within our families and within the context of incarceration. People might ask themselves, why are there so many people with disabilities incarcerated? We will not, however, arrive at the answer by looking at only one disability alone.

E. The Medical and Social Models of Disability

Bearing in mind both the definitions of disability above and the cross-disability view, it’s important to know that there are multiple models of looking at disability that currently tend to drive systems design. In this section, we will focus on the medical versus the social model of disability.

The medical model of disability relies on viewing disability as something that is wrong, or broken, with the person.[37] This approach relies on the identification of a person’s diagnosis or medical label. Under this model, a person with a disability is seen as “incapable.” The medical model has been used to propagate stigma and segregation of people with disabilities for centuries, and it has been used to justify criminalization on the basis of the disability label. It is also the model that tends not to recognize people with disabilities as people in charge of their own lives.

In contrast, the social model of disability is not about fixing people but about fixing barriers in society. Disability studies scholars credit British academic Mike Oliver with framing and conceptualizing the social model of disability in his 1990 book The Politics of Disablement.[38] While the origin of this model emerged in the 1960s, it was Oliver who clearly framed it in the sense that it is used today. The social model holds that disability is not created by the person’s condition; rather, disability is the barriers forced onto the person by society.[39]

Under this model, a person with a disability is like anyone else, except they need the social structures of access to thrive. This can be as straightforward as accessible building design, a wheelchair, a hearing aid, Braille, lighting or a cane, to name a few such structures. With invisible disabilities, access can include more time and more space for de-escalation or processing.

The social model of disability holds that all people can equally participate in society with the right accommodations in place. The problem is not the individual but whether society has created the right environment and eliminated artificial barriers. The biggest problem facing people with disabilities is that society isn’t flexible enough to accommodate all the differences in people – and that’s a serious system design issue for the criminal justice system.

F. The Criminal Justice System and Disability Clash

As you might imagine, disability tends to clash with the criminal justice system; disability by its very nature is a state of non-compliance. A clash can start very early on in the contact process. At first point of contact with 911, a person with a disability may be misunderstood and diagnosed or categorized as a person requiring an elevated police response. The person may be perceived as someone who isn’t “normal” and may be “unpredictable” and sometimes even categorized as an “unknown threat.”

Command culture is fertile ground for disability clash and law enforcement in particular may not immediately spot any disability issues. This kind of conflict leads to harm and sometimes death of people with disabilities. For example, when a police officer shouts commands at a deaf person and the person does not follow the officer’s directions, the deaf person might be shot. A person with cognitive processing issues likewise may not understand or interpret commands in a way that appears compliant to an officer, and therefore is put at risk for factors beyond their control. Command culture also does not tolerate physical disability well; an officer conducting a traffic stop may order a person who can’t walk to get out of a car.

Elliot Oberholtzer of the Prison Policy Initiative has highlighted that courts also can be a place of disability clash for people with disabilities in jail, who are most often awaiting trial. “For those disabled people who do need to interact with the courts,” he said, “they deserve the treatment that the United States has committed to providing in the Bill of Rights: a speedy trial, legal representation and to be informed of the nature and causes of the accusations against them. When courts fail to provide these basic rights for disabled people accused of crimes, they demonstrate clearly that our society treats disabled people as second-class citizens.[40]

Another area of disability clash is within the jail. Frequently, people with disabilities come into a jail that is not equipped to screen their disability appropriately or immediately accommodate; this leads to further harm and sometimes death. Many disability activists agree that inadequate medical care in custody is responsible for many of these preventable deaths.[41] According to the Prison Policy Initiative, the top cause of death in jail is suicide and less than half of jails are equipped to offer people who are detained mental health treatment services.[42] When speaking with impacted community members locally, all reported not having adequate disability accommodation supports in place while in jail. Furthermore, involvement in the criminal justice system can cause new disabilities for a person, most notably affecting their mental health.

Margo Schlanger gets to the root of the deeply individual nature of disability as it battles with the compliance culture in a jail or prison setting:

“Incarceration isn’t easy for anyone. But sharply limited control over one’s own routines and arrangements make life behind bars particularly difficult for prisoners with disabilities. Prisoners with mobility impairments, for example, “cannot readily climb stairs, haul themselves to the top bunk, or walk long distances to meals or the pill line. … Prisoners who are deaf may not hear, and prisoners with intellectual disabilities may not understand, the orders they must obey under threat of disciplinary consequences that include extension of their term of incarceration. And prisoners with intellectual disabilities may be unable to access medical care or other resources and services, because officials require written requests and they are illiterate.”[43]

Jail intake is a significant area of opportunity to understand the disability demographics of those being booked and also to begin proactively asking people if they need a disability related accommodation. This opportunity is made more complicated by the fact that it can be difficult for jails to screen and accommodate the vast array of needs of people entering the door on any given day. Some jails, such as Cook County Jail, are simply handling enormous volume on a daily basis; the average daily count of Cook County is 6,100.[44] However, from a social model standpoint, level of difficulty or time required is insufficient justification to not provide someone with the very things they need to survive. Realistically, how should these competing priorities be balanced?

All of this highlights the importance of understanding disability more in-depth from a social model viewpoint and to prioritize creating policies and protocols which focus on access being provided across disabilities in all settings.